Agression Atelier

Fashion, inseparable from design and art, seems to oscillate between an aesthetic exploration developed through time and how this relates to the material and social needs of an era. To understand why we dress the way we do we must look back into the past and understand garments not as relics but as living artifacts that tell us about the life and culture of people that we have much in common with. Since 2017, Aggression Atelier created pieces inspired in traditional Japanese fashion that adapts to contemporary needs exploring the relationship between style and functionality. We interviewed creator and designer Mariana Plata and talked about her brand, her relationship with Japanese culture and the transformative quality of fashion.

1) How did the project come to be and how has it changed?

When I studied fashion design I wasn't sure where that was going to lead me but my first contact with japanese fashion was because i came upon some japanese magazine about gothic, gothic lolita, decora and alternative fashion. Some friends of mine introduced me to visual kei music that was influenced by glam-rock and kabuki. I was impressed with how different it was from European fashion: the different concepts of proportions, textures, asymmetry(...) It was until 2017 that I got more immersed in traditional Japanese culture when I started going to the festivals organized by the Asociación México Japonesa ( Mexico-Japanese Association) and attended as a vendor where a uniform was required. I chose and redesigned a happi garment traditionally worn by farmers in the Edo period and it caught the public’s interest. I decided to focus on redesigning traditional pieces.

From time to time I try to update myself with some course or workshop but I'm mostly self-thought, more so on my research. Being a designer has allowed me to know a little bit of everything. I do make prototypes when making a design and I’m a perfectionist. For example, when I was analyzing the hakkama, a garment used for kendo, the design wasn't working for me and for modern needs so I modified and played with it. People really like these new pants because of the fabric and silhouette. I’m very knestesic so having the Centro Histórico as an option when shopping for textiles is like a blessing. I like to use textiles from Mexican factories, even if there aren’t so many.

2) How has your brand developed creatively? What inspires you?

Before I was afraid to experiment: I started making sweatshirts but never imagined that garments used in Japan 300 years ago could work.(...) What’s interesting is that these pieces don't look completely traditional but are tailored to contemporary needs.(...)What’s important is not just selling them but talking about their history. I was inspired by the exhibits in the Mexico-Japanese Association, samurai armor shows, their silhouettes and proportions. I’m also inspired by kabuki theater and their textile motifs as by the work of the designer Jun Takahashi and his brand Undercover.

3) At the core of the project is japanese-inspired design? ¿What has been the public’s response from an intercultural perspective?

Our motto as a brand is “We share with you the passion for Japan ''. Before starting with the brand, in 2016 I had the chance to attend a congress in the Japanese Embassy with the then ambassador Yasushi Takase and he told us how Mexican entrepreneurial projects that wanted to spread Japanese culture should be ambassadors of said culture, strengthening the relationship between Mexico and Japan. Mexican audiences that have this common interest regard our brand in high values and identify with the concept. For example, I used to work in a school near Iztapalapa at six a.m. so I had to take a bus with a lot of imposing men with their face or head covered from the cold, with big jackets and hands in their pockets. I remember thinking in my commute that they were like some kind of urban ninjas. From that I started designing the “ninja sweatshirt”, the first brand design. When you put it on there is something ludic and transformative about it.

I tried to make every garment genderless. I know it is hard because of the average proportion of the Mexican body and how it’s nearly impossible to satisfy the needs of the market regarding sizes. When you see a garment the size is as important as the design.

4) What can we expect from Aggression Atelier in the future?

Coats, jackets and windbreakers are my favorite pieces of clothing so I would like to focus on designing that type of functional pieces.(...) I feel that when you wear a coat you transform yourself and that allows me to make my vision come to life. I’m also looking to take a tailoring course since the technique and finishings are helpful for my craft.

Agression Atelier

Agression Atelier

La moda, inseparable del diseño y el arte, parece oscilar entre la exploración estilística que se desarrolla con el paso del tiempo y cómo esto se relaciona con las necesidades no solo materiales, sino sociales de cada época. Para entender porque nos vestimos como nos vestimos hace falta mirar hacía el pasado y entender las prendas no como reliquias, sino artefactos vivos que nos hablan de la vida y cultura de las personas con las que compartimos más de lo que se ve a simple vista. Desde 2017 Agression Atelier se ha dedicado a la creación de piezas inspiradas por la moda japonesa tradicional pero adaptadas a las necesidades contemporáneas, explorando la relación entre lo funcional y lo estético. Conversamos con su creadora, la diseñadora Mariana Plata, sobre la visión de su marca, su relación con la cultura japonesa y la capacidad transformativa de la moda.

1)¿Cómo se originó el proyecto y cómo ha cambiado con el tiempo?

Yo de inicio estudié diseño de modas y no tenía muy claro hacía dónde me iba a dirigir pero mi primer contacto con la moda japonesa fue porque llegaron a mis manos unas revistas japonesas sobre moda gótica, gothic lolita, decora, de subculturas alternativas, además de que unos amigos me introdujeron a la música visual kei que está influenciado por el glam-rock y el kabuki. Me impresionó lo distinta que era de la moda europea: la distinta concepción de las proporciones, las texturas y asimetrías.(...) Fue hasta 2017 que tuve más contacto con la cultura tradicional japonesa ya que me incorporé a los festivales de la Asociación México Japonesa donde nos pedían utilizar un uniforme. Yo elegí y rediseñé el happi, una pieza de trabajo tradicional utilizada por los campesinos en el periodo Edo y la gente comenzó a preguntar por ellos y a interesarse. Decidí enfocarme entonces en diseñar piezas tradicionales.

Cada cierto tiempo intento actualizarme con algún curso teórico o taller práctico, pero soy mayormente autodidacta, más en en proceso de investigación para realizar las prendas. Mi formación como diseñadora me ha hecho aprender de todo un poco, etc. Sí hago prototipos cuando hago un diseño y suelo ser muy perfeccionista. Por ejemplo para el pantalón que salió este año estuve analizando la hakama de kendo, pero el diseño no se adapta a lo actual y lo fui modificando y jugando con el diseño original. Estos pantalones les han gustado mucho a las personas por el tipo de silueta y el textil. Soy muy kinestésica, por lo que es casi una bendición tener el Centro Histórico para poder comparar textiles, me gusta meter muchos textiles de marcas mexicanas a pesar de que hay pocas fábricas.

2)¿Cómo ha sido el desarrollo creativo de la marca? ¿Qué te inspira?

Antes tenía mucho miedo a experimentar: había comenzado a hacer sudaderas pero nunca me imaginé que retomando prendas que se utilizaban hace 300 años en Japón estas funcionaran. (...) lo interesante es que la prenda no se ve completamente tradicional pero que es adaptable para las necesidades actuales.(...) Lo importante no solo es vender la prenda sino platicar sobre su historia. Me inspiraron mucho, en la misma Asociación Japonesa y sus exposiciones, los shows con armaduras samurai, sus siluetas y proporciones. Me inspiran también el vestuario y las paletas de color de las peliculas de Akira Kurosawa, las siluetas del teatro kabuki y sus motivos textiles al igual que el trabajo del diseñador Jun Takahashi y us marca Undercover.

3)En el centro del proyecto está el diseño inspirado por la estética japonesa, ¿Cuál ha sido la respuesta del público desde lo intercultural?

Mi lema como marca actualmente es “compartimos contigo la pasión por Japón”. Antes de empezar como marca en 2016 tuve la oportunidad de ir a la embajada de Japón en México aún congreso con el entonces embajador Yasushi Takase quien nos dijo que como empresas mexicanas que buscábamos difundir la cultura japonesa debíamos ser embajadores de esta cultura, para compartirla y fortalecer la relación México-Japón. El público méxicano que comparte este interés valora mucho a la marca y se identifican con el concepto. Por ejemplo, yo trabajaba en una escuela por Iztapalapa y me iba a las seis de la mañana en camión, donde también se subían muchos hombres que se veían imponentes y con el rostro o la cabeza tapada por el frío, con sudaderas amplias y las manos en los bolsillos. Recuerdo haber pensado en mi traslado que eran como ninjas urbanos y de ahí se comenzó a crear la sudadera ninja, el primer diseño de la marca. Al ponerse la prenda hay algo lúdico y transformativo sin llegar a ser un disfraz.

Intento que cada prenda que hago sea sin importar el género. Sé que es difícil por la proporción del cuerpo de los mexicanos aunque es casi imposible satisfacer las necesidades del mercado en cuanto a tallas. Cuando ves una prenda lo importante no es solo el diseño pero también la talla

4)¿Qué podemos esperar de Agression Atelier en el futuro?

Los abrigos, las chamarras y los rompevientos son mis prendas favoritas entonces me gustaría enfocarme en diseñar este tipo de prendas funcionales(...). Siento que cuando te pones un abrigo te transformas y me permite plasmar mi visión. También busco actualizarme con un curso de sastrería porque la parte de la técnica, tela y acabados me ayuda.

Grupo Máxico: oneiric journey, collective dreams

Artistic practice, probably since forever, is inherent to human nature. What changes is the way we experience it, if we call ourselves artists from specific art-production dynamics and if what we do is talk about the self and what surrounds us. Even in the most close-knit art circuits as in the more open ones, the concept of collectivism is not just recurrent but even necessary for the recognition of the artist beyond the individual.

Formed by the Mexican artists Bral Sorchini and Sergio Heredia, since 2017 Grupo Máxico focuses on artistic production and communication. From this work came the creatión of a collective, LOS MÁXICOS, composed by 21 multidisciplinary artists who are guided and get their inspiration from the Choko Tuukul (choko= crazy in maya/ tuukul= reflection or thought in maya) text. Through the discipline of dreams (Tenonotialistli Wayak’) the artists explore not just the meaning of their own dreams and experiences but they integrate them to their creative process. This holistic and ludic spirit is not inclusive of the project, but is alive in the praxis of both artists. In “@045345” (2010-2011) Sergio synthesizes his dreams via twitter as a continuation of his oneiric journal. Bral constructs an ephemeral and calligraphic exercise using a water pencil in “Zacate-fude” (2015-). We interviewed them to know more about LOS MÁXICOS, cultural management and the concept of the “collective” in the art world.

-How was the group created? The artists’ work is related to a theme of particular ethos?

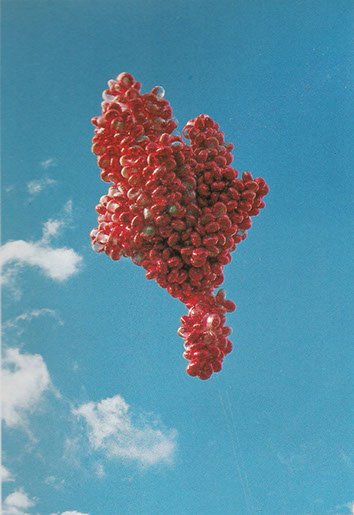

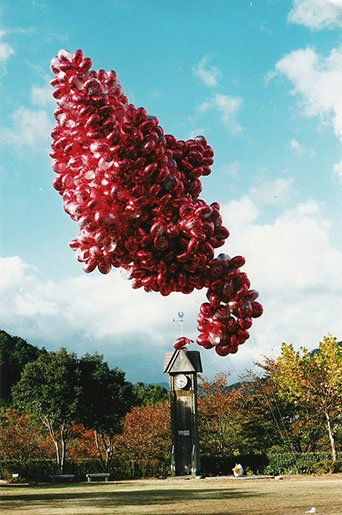

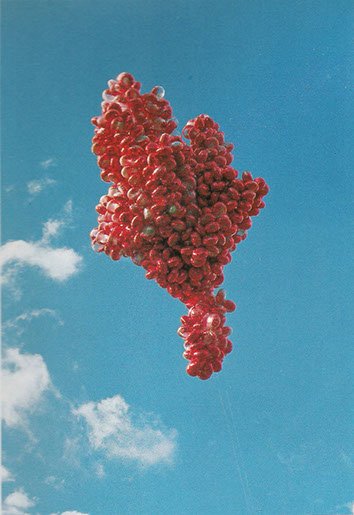

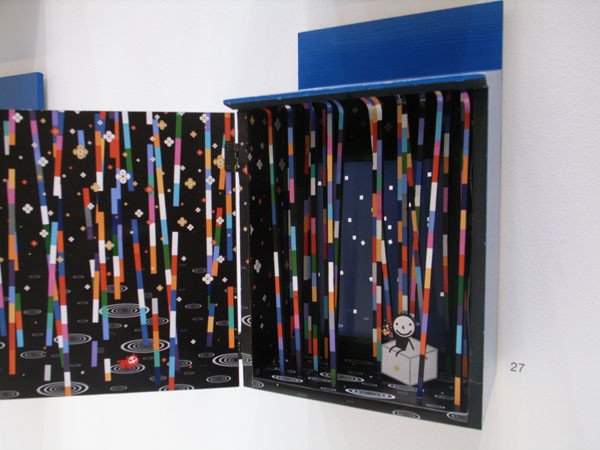

S: Our project is called LOS MÁXICOS: there are 21 that we work with for a collective exhibition in November. We've been doing this for a year. Inspired from a text, we pick a theme and we give them creative freedom through performance, video, installation. This reunion of artists has to do with the ancestral dream discipline (Tenonotialistli Wayak’) where in the moment of dreaming, we carry what is lived awake to the dream and during the dream we remember what was lived awake. For this group this is a cycle: you can be resting while awake, or awake asleep, a way to deal with reality through your own experience asleep and awake. Our last exhibit was called “El Futuro de la Magia '' and we talked about the different types of magic there are: from magic tricks, coincidences, the magic of love, technology, money exchange, nature.

Salvador Toledo, Natura Naturata, El Futuro de la Magia

B: Usually we work with social themes. The dream discipline talks about waking through dreams and through vigil from the social, cultural, political, artistic and philosophical aspects. In this exhibit we talked about the different types of magic that exist in daily life, how they affect us and our habits and behavior.

S: We don't want to always talk about magic, we want to give every participant the possibility to explore a particular subject. I’m a filmmaker and Brenda is an artist but she was going to become an astrophysicist.(...) I really like cinematographic language but also theater and staging. In “El Futuro de la Magia” we reached our audience in a very scenic way: pieces were for sale but also given away, allowing the public to take them. We are not talking about a marketing or selling project since much of contemporary art is made for the enjoyment of the elites. We don't think about that. We understand that the enjoyment of art has to be for everyone. We sold two pieces but gave away fifty.

-What surprises have you encountered on the crossroad between the artist role and cultural management?

B: Our collaborative work has to do with the fact that we are artists as well and we know that everyone has different criteria about time and space, we don't work at the same pace and we respect that. That’s why we take our time planning an exhibit because we want to take into account everyone’s process. We try to give enough space so everyone finishes in time for the exhibit.(...) As the collective managers we work with them side by side. We’ve realized this isn’t a hard process because we know how they work and we are empathetic, as the other way around. A lot of them perfectly understand our work.

S: On the other hand, what's complicated can be the venue and space. It isn’t easy to find them because the collective has grown and we don’t want to limit the artists.

B: What we want is to be reciprocal with the good response they have given us as a collective, not limiting us to space or technique, each one is free to do as they imagine.(...) Usually its asked to narrow things down. In our case we need to go from something general so the artists can find their own particular interest. Often artists thank us for the freedom to create whatever they want. To be able to understand from cultural management that every artist has a specific process makes everything flow.

-¿What is the future of Grupo Máxico and LOS MÁXICOS? What can we expect of your upcoming exhibition?

S: Our next exhibition is called “Nuevas Constelaciones”. In it the power of sight, of looking and gazing, is primordial because through it we can make connections between the collective and the public. Even if the topic can be vague, its openness makes it limitless. In “Nuevas Constelaciones' ' we want to talk about encounters, agreements, how is it that throughout space and time everyone has agreed on the existence of 88 constellations. ¿How do we make said constellations? Through collaboration between artists as they communicate to create a collective pieze, not from quite an individualistic perspective.

Olga Siqueiros, Natura Natus (Autorretrato post mortem), El Futuro de la Magia

Grupo Máxico: viaje onírico, sueño colectivo

La práctica artística, posiblemente desde siempre, es intrínseca a la condición humana. Lo que será una variable es cómo esta nos atraviesa, si nos nombramos artistas desde dinámicas de producción del arte particulares y si aquello que hacemos habla sobre nosotros y lo que nos rodea. Tanto en los circuitos del arte más cerrados como en aquellos de carácter más plural, la figura del colectivo o del grupo es tanto recurrente como incluso necesaria para el reconocimiento del artista más allá de un individuo.

Conformado por los artistas mexicanos Bral Sorchini y Sergio Heredia, desde 2017 Grupo Máxico se dedica a la producción y difusión artística, esfuerzos que dos años después los han llevado a la creación de LOS MÁXICOS, un colectivo multidisciplinario compuesto actualmente por 21 artistas, cuyo eje rector de trabajo es el texto del Choko Tuukul (choko = loco en maya/ tuukul = reflexión o pensamiento en maya). A través de la práctica de la disciplina del sueño (Tenonotialistli Wayak’) los artistas exploran el significado de los mismos al igual que sus vivencias, integrando todo esto de forma activa a su proceso creativo. Este espíritu tanto integrativo como lúdico no es exclusivo del proyecto, pero existe latente en la praxis de ambos artistas. En “@045345” (2010-2011) Sergio realiza una síntesis vía twitter de sus sueños como continuación de una bitácora onírica. Bral conjuga en “Zacate-fude” (2015-) un ejercicio caligráfico y efímero con un pincel de agua. Entrevistamos a estos artistas para indagar sobre LOS MÁXICOS, la gestión cultural y el concepto de lo colectivo en el mundo del arte.

-¿Cómo se creó el grupo y los artistas que lo componen? ¿Su obra existe dentro de una línea temática o un ethos particular?

S: Nuestro proyecto se llama LOS MÁXICOS: son 21 artistas con los que estamos trabajando para tener una exposición en conjunto en Noviembre, es lo que llevamos haciendo desde hace ya un año. Se les pone una temática y se les da libertad creativa, puede ser performance, video o instalación a partir de un texto. Esta reunión de artistas tiene que ver con una disciplina ancestral que habla del sueño (Tenonotialistli Wayak’) donde al momento de soñar, llevamos lo que se vive en la vigilia al sueño, y a la hora del sueño recordamos la vigilia. Para el grupo esto es un ciclo: puedes estar descansando despierto, o despierto dormido, una forma de manejar la realidad por medio de tus propias vivencias al estar despierto y al estar dormido. La última exposición que tuvimos se llamó “El Futuro de la Magia” y hablamos de los distintos tipos de magia que hay: desde los trucos de magia, las coincidencias, la magia del amor, la tecnología, del intercambio monetario, la naturaleza.

Salvador Toledo, Natura Naturata, El Futuro de la Magia

B: Normalmente se trabajan temas sociales. La disciplina del sueño habla del despertar mediante el sueño y la vigilia desde los ámbitos social, cultural, político, artístico y filosófico. Cada uno de los artistas se interesa en estos temas. En esta exposición hablamos de estos distintos tipos de magia que se dan en la vida cotidiana, cómo todo esto nos marca y se establecen ciertas pautas de acción o comportamiento en cada uno de nosotros.

S: No queremos siempre hablar de la magia, queremos darle a cada uno de los participantes la posibilidad de explorar un tema particular. Yo soy cineasta y Brenda es artista pero iba a ser astrofísica.(...)Me gusta mucho la gramática cinematográfica pero también el teatro, las puestas en escena. En “El Futuro de la Magia” nos acercamos al público de una forma muy escénica: estuvieron a la venta piezas pero también la regalamos, haciéndoles participar para que se las llevaran. Nosotros no estamos hablando de un proyecto de mercadotecnia ni venta sino de disfrute porque mucho del arte contemporáneo se caracteriza por ser para el disfrute de las élites(...) No lo tomamos en cuenta. Sabemos que el disfrute del arte tiene que ser para todos. Vendimos dos piezas pero regalamos cincuenta.

-¿Con qué sorpresas se han encontrado en la encrucijada entre la labor del artista y la gestión cultural?

B: Nuestro trabajo en colaboración tiene que ver con que nosotros también somos artistas y sabemos que cada uno como criterio tiene cierto tiempo y espacio, no todos trabajamos al mismo ritmo, buscamos respetar esto de cada uno. Por ello nos toma tiempo planificar una exposición porque queremos tomar en cuenta los procesos de cada uno de ellos. Procuramos dar espacios suficientes para que todos concluyan a un tiempo acorde a la exposición. (...) Como gestores del colectivo trabajamos con ellos de codo a codo. Nos hemos encontrado con que no ha sido un proceso difícil ya que sabemos como trabajan y somos empáticos con ellos y viceversa. Muchos de ellos entienden perfectamente nuestra labor.

S: Por otro lado lo complicado puede ser el venue, los lugares. No es tan fácil encontrarlos porque el colectivo ha crecido y no queremos limitar a los artistas.

B. Lo que queremos es ser recíprocos con la muy buena respuesta que nos han dado como colectivo, no limitarnos en ninguna cuestión de espacio o técnica, cada uno es libre de hacer lo que se imagine.(...) Normalmente se pide acotar. En nuestro caso necesitamos partir de la generalidad para que los artistas puedan ir acotando sus propios intereses. Ha sucedido muchas veces que los artistas nos agradecen la libertad de crear lo que quieran. Poder entender como gestor que cada artista tiene un proceso específico, hace que todo empiece a fluir.

-¿Cuál es el futuro de LOS MÁXICOS y de Grupo Máxico? ¿Qué podemos esperar de su próxima exposición?

S: La próxima exposición se titula “Nuevas Constelaciones”, en ella, el poder de la mirada se vuelve primordial ya que es a través de ésta que podemos crear conexiones entre el colectivo y el público. Aunque nuestro tema puede ser muy vago, esa amplitud permite no limitarse a ciertos temas. Estamos también invitando a personas de cualquier ámbito a colaborar ya que es otro tipo de mirada. Con “Nuevas Constelaciones” buscamos hablar de los encuentros, de los acuerdos, por ejemplo, cómo es que todo el mundo a través de los tiempos coincide en que hay 88 constelaciones. ¿Cómo realizamos nosotros estas constelaciones? Mediante la colaboración entre artistas, no es tan individualista, entre ellos se comunican para crear una pieza en conjunto.

Olga Siqueiros, Natura Natus (Autorretrato post mortem), El Futuro de la Magia

Melquiades Herrera: Objeto efímero y quehacer artístico

Objeto efímero y quehacer artístico

Melquiades Herrera es reconocido por su exploración performática desde lo cotidiano, la sátira, el humor y la parodia. Fue maestro de artes visuales y geometría en la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (UNAM) y en la Escuela de Diseño del INBA (EDINBA). También fue miembro fundador del colectivo No-Grupo activo de 1977 a 1987 junto con Rubén Valencia, Maris Bustamante y Alfredo Núnez. A pesar del gran valor de su obra, para el arte acción y conceptual en México a finales de siglo pasado, por la naturaleza del mismo, es solo recientemente que instituciones como el MUAC han hecho esfuerzos para documentar y revalorizar la carrera de este artista.

“En un momento determinado, la comicidad es subversiva(...)todo el mundo puede echar relajo pero no todo mundo puede hacer humor, el humor es una categoría estética de las más altas en el arte e incluso diría yo que es una herramienta fundamental del conocimiento humano.”

La obra de Herrera, popular y multifacética, es hasta la fecha profundamente relevante para encontrarnos y entendernos en una sociedad, una cultura, con un tan voraz y arraigado sistema de producción de objetos y, por lo tanto, de arte y cómo aunque esto parezca o muy atractivo o muy lejano, se refleja en nuestro día a día. Tanto es el caso que su trabajo es pivotal para la reciente “socially engaged-practice” o práctica socialmente integrada del arte donde la interacción social está en un mismo o nivel similar de valor que el arte mismo.

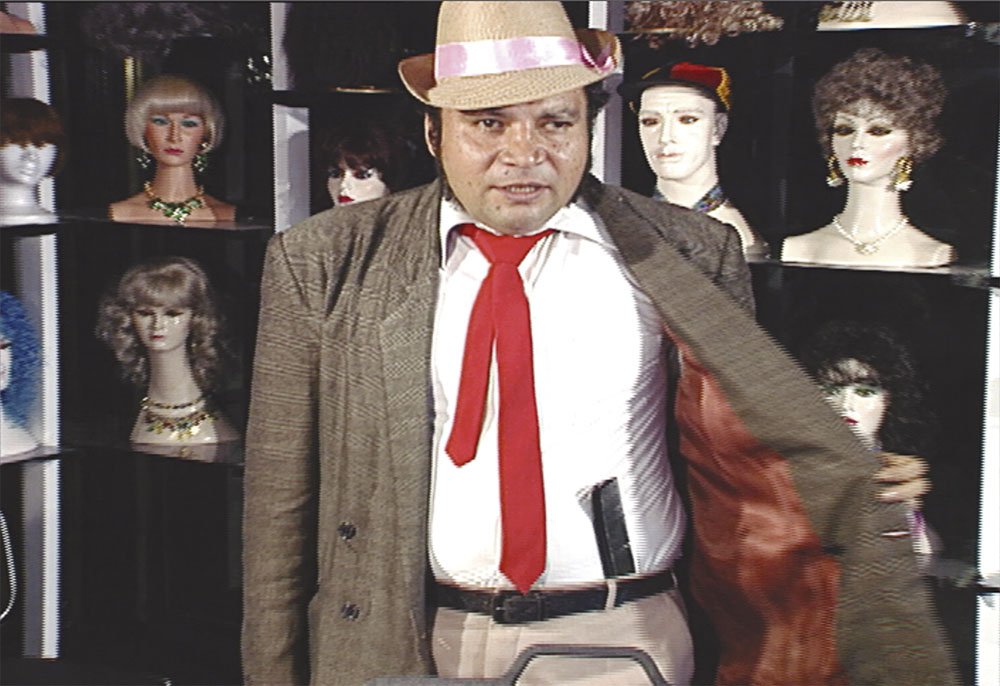

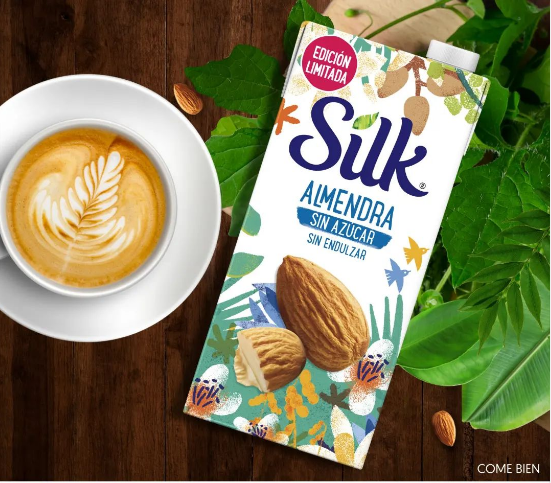

Por ejemplo, en 1978 aceptó el inexistente Premio Nobel de Arte y en 1993, siendo anfitrión de su propio programa de televisión en donde mostraba al público cómo utilizar diversos peines que traía en un maletín (Venta de Peines, 1993). En 1995 realizo un falso documental sobre el mercado negro en la Ciudad de México (Uno por 5, 3 por diez) y el 1997 un performace en el EDIMBA (The Museum of Modern Art Store Stand Melquiades Herrera) donde coloco un puesto de venta de objetos tipo “tienda de museo”.

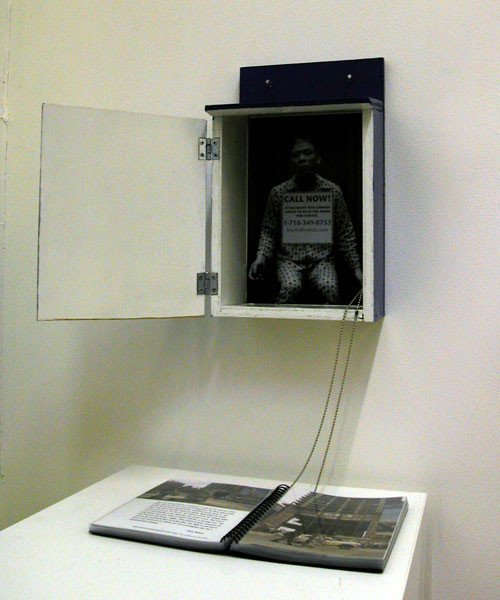

Venta de Peines, 1993.Aunque varias de sus obras, como en el caso del programa de televisión y el falso documental, estaban pensadas en un formato reproducible, muchas de sus acciones eran de carácter performativo y, por lo tanto efímero. En ellas, muy dentro de la lógica de ready-made pero llevándola más lejos, el artista cuestiona la utilidad que se le da a los objetos y por lo tanto su valor y significado, creando nuevos usos y funciones para estos.Esta propuesta es a su vez, no solo una crítica de nuestra sociedad y la cotidianidad, pero sobre los objetos y el quehacer artístico, dónde está el límite y como son las dinámicas mercantiles dentro del mundo del arte contemporáneo.

“Todo arte tiene una función en un momento determinado, cuando los ambientes sociales son muy solemnes el arte tiene que cumplir la función de solemnizar. Cuando Duchamp le pintó bigotes a la monalisa, igual que se hace en las sátiras a los candidatos a diputados o presidentes en los países como Francia o México, se trata de hacer un distanciamiento, la gente ha llevado a ver el arte de una manera demasiado solemne, como cuando oímos de los clásicos e imaginamos unos señores apolillados, pero para mi los clásicos están vivos(...) de la misma manera lo efímero o la forma efímera manifestada como frivolidad es una forma de restaurar la vitalidad de las cosas, la mirada primera sobre las cosas.”

Melquiades Herrera: Reportaje plástico de un teorema cultural (2018)La obra del artista entrelaza la performativo-efímero con lo material-físico: es tanto una exploración cultural de lo que nos rodea como un cuestionamiento sobre nuestros hábitos de consumo y vinculación emocional con los objetos. Gracias a la historiadora del arte Sol Genaro, en el 2015 llegaron al MUAC cien cajas que contenían objetos del artista, los cuales formaron parte de la exposición “Melquiades Herrera. Reportaje plástico de un teorema cultural” en 2018. Es difícil darle un nombre definitivo a esta colección de objetos, un híbrido entre acervo y cháchara, pero nunca un residuo. Genaro, en un texto sobre el artista, señala que para Melquiades Herrera el mismo acto de vivir la vida es en sí una acción performativa.

La labor titánica de crear y curar esa exposición responde profundamente a lo que el artista llamaba “estética de la vida”, la propia práctica artística inseparable del día a día, formulada desde ahí, con tantas posibles salidas como vivencias propias.

“Me niego a pensar que los objetos en particular son obras, la mayoría son cosas cotidianas; hay algunos firmados y podríamos decir que es obra, sin embargo, el grueso de las piezas son parte de un gran proyecto artístico y su importancia está en su conjunto, aislados no tienen sentido, pero en suma sí podemos pensarlos como testigos históricos de una época”,

-Roselín Rodríguez, integrante del colectivo Los Yacuzis, responsables de la curaduría de la exposición.

Melquiades Herrera, Las miniaturas me hacen llorar. Fondo Melquiades Herrera. Centro de Documentación Arkheia- MUACFuentes:https://artishockrevista.com/2018/04/08/melquiades-herrera-muac-mexico/https://revistaerrata.gov.co/contenido/melquiades-herrerahttps://gatopardo.com/arte-y-cultura/melquiades-herrera-muac/https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/socially-engaged-practiceMelquiades Herrera: Ephemeral object and artistic endeavor

Melquiades Herrera is known for his perfomatic exploration of humor, parody, satire and daily life. He was a visual arts and geometry teacher in the National Plastic Arts School (UNAM) and in the Design School (EDINBA). He was also a founding member of the NO-Grupo collective, active from 1977 to 1987, with Rubén Valencia, Maris Bustamante and Alfredo Núnez. Despite the value his work has for the development of performance and conceptual art in Mexico at the end of the last century, because of its nature, only recently institutions like the Universitary Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) have made an effort to document and revalue this artist's career and contributions.

“In a specific moment, comedy is subversive(...) everyone can mess around but not everyone can make humor. Humor is an aesthetic category, or the highest in art and I would even argue that it is a fundamental tool for human knowledge.”

Herrera’s work comes in various shapes and forms. For example in 1978 he accepted the (nonexistent) Nobel Art Prize and in 1993 hosted his own TV show where he showed the audience how to use some combs he carried on a case (Venta de peines, 1993). In 1995 he made a mockumentary on the black market in Mexico City (Uno por 5, 3 por diez) and in 1997 a performance in the EDIMBA (The Museum of Modern Art Store Stand Melquiades Herrera) where he sold museum gift shop-type objects in a street stand.

Herrera’s work, popular and multifaceted is, till this day, very relevant to the understanding of our own society, and culture, that has such voracious and ingrained system of object.production and therefore, of art, and how even if all of these seem to foreign or abstract, reflects on our daily life. His work is pivotal for the development of the recent socially engaged-practice in the arts, where “social interaction is at some level the art.”

Venta de Peines, 1993Even if some of his works exist in a playable format, like the TV show or the mockumentary, much of his actions were performative and ephemeral. With a ready-made logic, but going beyond, the artists question the use we give to objects and, therefore, their value and meaning, creating new possibilities and functions for them. This proposition is not just a criticism to our daily life and society but to the objects and their relationship with the artistic practice, the market dynamics in the contemporary art world.

“All art has a function in a determined time, when the social environments are very solemn, art has to fulfill its function to solemnize. When Duchamp painted a mustache on the monalisa, as satire to politicians and presidents is done in countries like France and Mexico, it's about creating distance. People have made art to be seen as too solemn, like when we hear about the classics and we imagine old decrepit men, but for me the classics are alive(...) in the same way the ephemeral or the ephemeral way manifested as frivolity is a form of restoring the vitality of things, the first look on things.”

Melquiades Herrera: Reportaje plástico de un teorema cultural (2018)The artist’s work links the performatic-ephemeral with the physical-material: is a cultural exploration of what surrounds us and an interrogation about our consumption habits and the emotional bond we create with objects. Thanks to the art historian Sol Genro, in 2015, a hundred boxes filled with objects owned by the artist arrived at the MUAC (Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo) and later on were presented in the exhibit “Melquiades Herrera. Reportaje plástico de un teorema cultural” in 2018. It’s hard to give an accurate name for this collection of objects, between acquis and junk, but never residue. Genaro, in a text about the artist, says that for Melquiades Herrera the act of living life has a performative act in itself. The herculean task to create and curate this exhibit deeply responds to what the artist calls the “aesthetic of life”, how his own artistic practice was inseparable from daily life, actually constituted from there, with so many possibilities as his experiences.

“I refuse to believe that these particular objects are works, most of them are ordinary objects; some are signed and we could say they are works but, most of them are part of a big artistic project and collectively they matter, alone they make no sense, but together we can think of them as historical witnesses of an era.”

-Roselín Rodríguez, member of Los Yacuzis collective, responsible for curating the exhibit

Melquiades Herrera, Las miniaturas me hacen llorar. Fondo Melquiades Herrera. Centro de Documentación Arkheia- MUACCecilia Bernal: about Mercarte, Branding Art and social responsability

The unparalleled technological development of the recent years and the economic and artistic practices born from it have created a series of questions related to the value for art, design and publicity and the consumption of cultural products in a world like ours. New opportunities and niches converge in art and publicity and even if naviting this two spheres might be difficult, Mercarte, a cultural management and Branding Art agency founded and directed by Cecilia Bernal, have succeeded in creating strategies not just to reconcile, but to benefit from these new spaces and possibilities that are not just attractive to the consumer but allow artist to fully use their creativity. We interviewed Cecilia about her ideas on this project, the future of Branding Art and cultural management's social responsibility.

-Where does the idea for the Mercarte project comes from? What are some of the strategies that have allowed you to create a bridge between the world of publicity and the world of culture and the arts?

“After a long trajectory as a publicist and being passionate about art for a lifetime, Mercarte was born 7 years ago when i decided to fund the first agency specialized in Branding Art. We link brands with the art and culture world from a 100% perspective.

The strategies come to life through the artists’ talent in different disciplines like: muralism, painting, illustration, photography, fashion design, ceramics, textile design and others; and through innovative actions like the intervention of products/packaging with art, murals (with QR and RA virtual tech), projects for taking back the public space, influencers, social media content and valuable consumer experiences. We recently have our eyes on NFTs.”

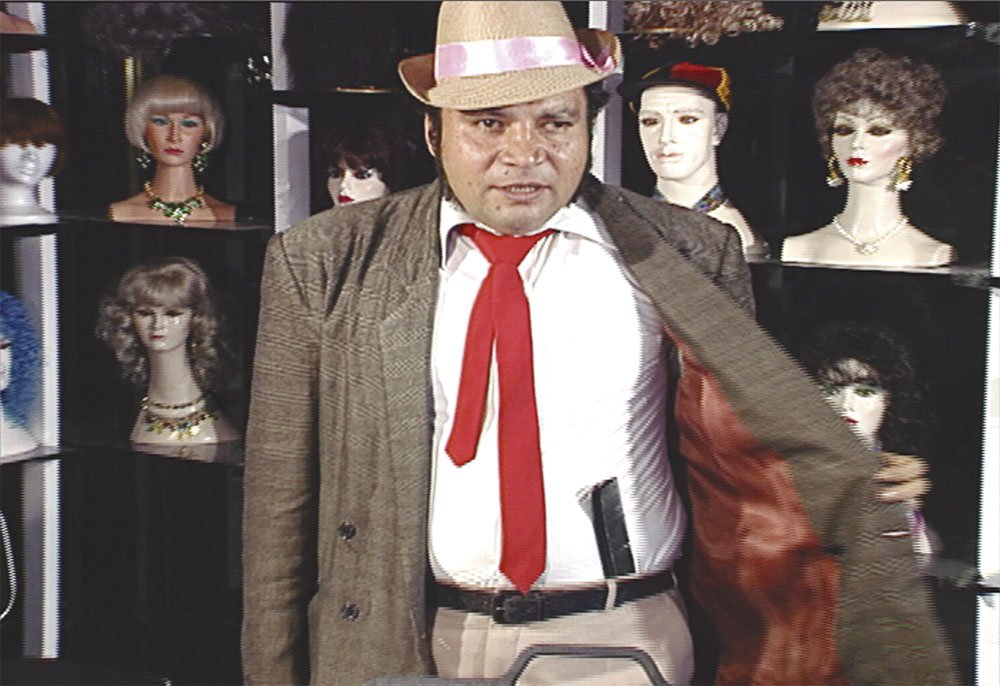

Mercarte’s collaboration with Hershey’s for the latest International Woman’s Day-Branding Art is the main part of your work. Throughout your trajectory has your idea or vision of this practice changed? What is the future of Branding Art?

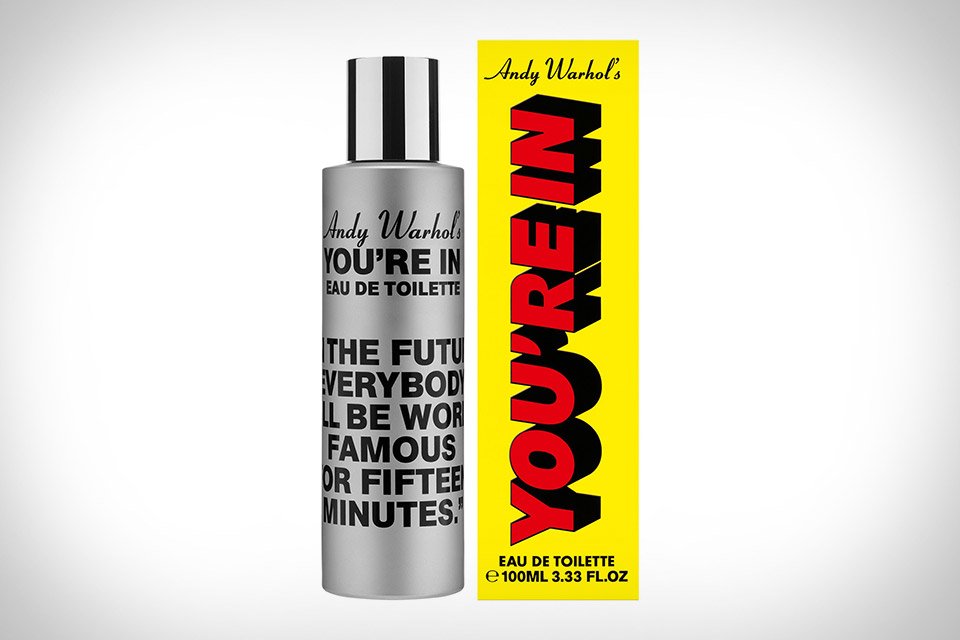

”Branding Art as an artistic practice is not new, we can go back to the first commissioned creations from renowned artists like the Chupa Chups lollipop logo by Slavador Dalí, the Caixabank logo by Miró and the iconic Absolut bottle intervention by Andy Warhol. What is actually new is that in the seven years Mecarte has become an agent of transformation in Branding Art, via strategic vinculation, going beyond an sporadic intervention but adding actual value to the brand, the consumers, the general public and of course, the artists.”

-From your perspective, What are the current challenges of cultural management?

”The main challenges I see are related to funding, promotion,communication and technology. To solve the first problem, we culture managers should make projects that actually add value so the public and mainly private sector can see them as opportunities that contribute to their objectives, providing economic resources and other forms of support like and outreach. As for technology, cultural consumption has everything to do with that. As cultural managers it is necessary to learn, understand and stimulate the use of new technologies and platforms, like RA and RV, the metaverse and NFTs.”

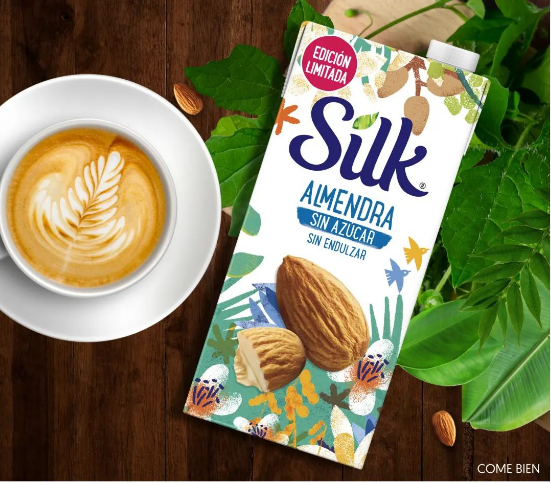

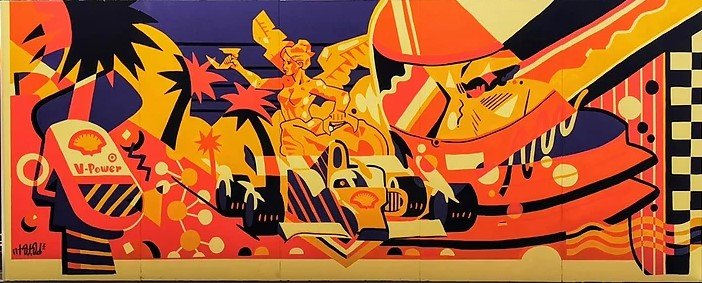

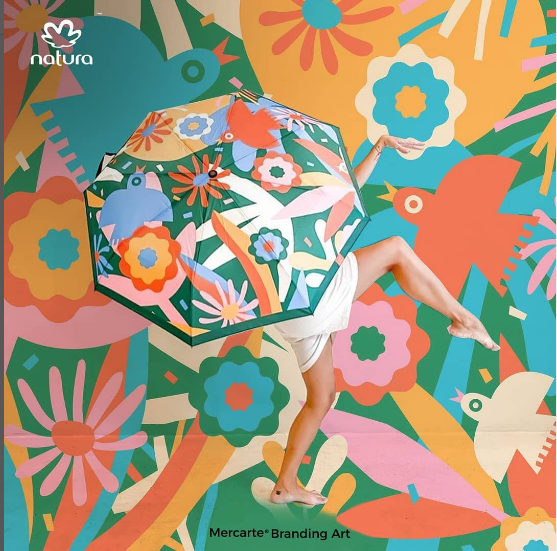

Mercarte has recently collaborated with Silk, McCormick, Natura, Shell and many others.

-Could you tell us about the Art for Life Foundation (Fundación Arte por la Vida)? What is the relationship between artistic practices and social responsibility?

“I am a firm believer that art is an important agent for social change and 6 years ago I created the Arte Por la Vida social program, a non-profit foundation and an authorized donor. Its objective is to make art and its virtues available to vulnerable populations (specifically to children and young people in homes and elderly adults that live in asylums).

Arte por la Vida is an example of the necessary relationship that exists between art and social responsibility because it allows individual transformation to be amplified collectively in society.

Our activities include guided visits to exhibitions, museums, galleries and theater functions, as art workshops with renown artists. Till this day, Fundación Arte por la Vida has benefited more than 1500 vulnerable persons in Mexico City, Veracruz and Morelos.”

Cecilia Bernal: sobre Mercarte, el Branding Art y la responsabilidad social

El desenfrenado desarrollo tecnológico de los últimos años y las prácticas económicas y artísticas subyacentes a este han dado cabida a una serie de cuestionamientos sobre el valor del arte, el diseño, la publicidad y el lugar del consumo de la cultura en un mundo como el nuestro. Nuevas oportunidades y nichos convergen en lo artístico y lo publicitario y aunque pareciera difícil navegar estas dos esferas, Mercarte, la agencia de Branding Art y gestión cultural Mercarte fundada y dirigida por Cecilia Bernal, ha logrado crear estrategias para no sólo conciliar, pero aprovechar estos nuevos espacios y posibilidades no sola atractivas para los consumidores pero que permitan explotar la creatividad de los artistas. Entrevistamos a Cecilia sobre la idea del proyecto, el futuro del Branding Art y la responsabilidad social de la gestión cultural.

-¿Cómo nace la idea del proyecto de Mercarte? ¿Cuáles son algunas de las estrategias que te han permitido crear vínculos entre el mundo de la publicidad y el del arte y la cultura?

“Mercarte nace hace 7 años, cuando después de una larga trayectoria como publicista y una vida siendo apasionada del arte, decidí emprender y fundar la primera agencia especializada en Branding Art, en la cual vinculamos a las marcas con el mundo del arte y la cultura desde un punto de vista 100% estratégico.

Las estrategias cobran vida a través del talento de artistas de diferentes disciplinas como: muralistas, pintores, ilustradores, fotógrafos, así como diseñadores de moda, ceramistas, diseñadores textiles, entre otros; con innovadoras acciones como la intervención de productos/packaging con arte, murales (incluso con tecnologías aplicadas como RA, QR, virtuales), proyectos de recuperación del espacio público, influencers, contenidos para redes sociales y experiencias de valor para los consumidores; recientemente tenemos la mirada en los NFT. “

Colaboración de Mercarte con Hershey’s para su útlima campaña del Día de la Mujer-El desarrollo de Branding Art es parte central de tu trabajo. ¿A lo largo de tu trayectoria se ha transformado tu idea o visión de esta práctica? ¿Cuál crees que será el futuro del Branding Art?

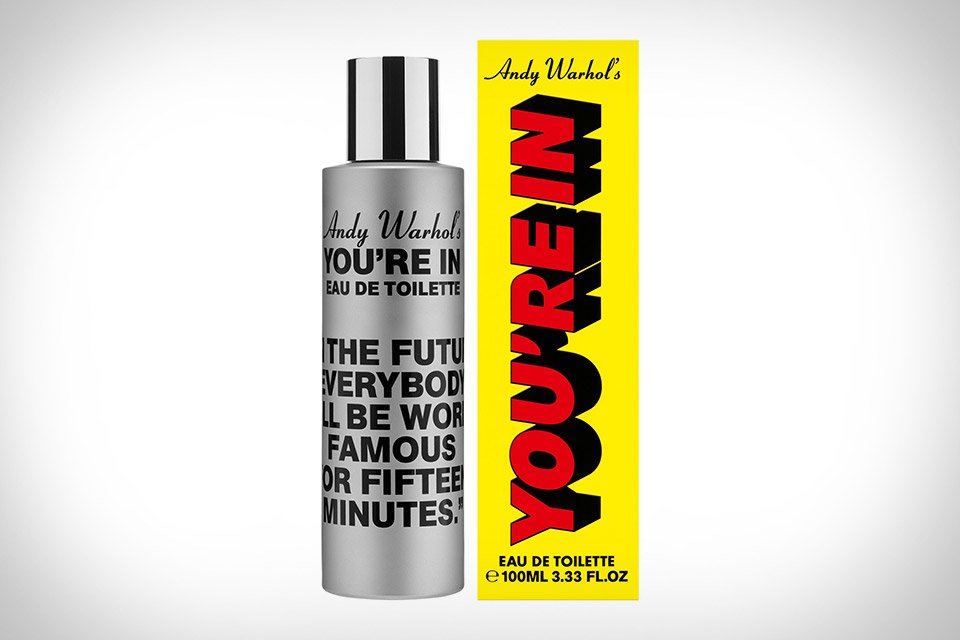

“El Branding Art como práctica en el mundo del arte no es reciente, nos podemos remontar a las primeras creaciones comisionadas por marcas con reconocidos artistas como el logotipo de la paleta Chupa Chups a cargo de Salvador Dalí, el logo de Caixabank por Miró o la icónica intervención de la botella de Absolut por Andy Warhol.

Lo que sí es reciente y que en estos 7 años en Mercarte nos hemos convertido en agentes de transformación del Branding Art, es la vinculación de forma estratégica, que no quede en una intervención esporádica, sino que de verdad le sume valor a la marca, a sus consumidores, público en general y por supuesto a los artistas.”

-Desde tu perspectiva, ¿Cuáles son los retos actuales de la gestión cultural?

“Los principales retos que veo son principalmente los relativos a la financiación, difusión y la tecnología.

Para resolver el primero, como gestores culturales debemos realizar proyectos que verdaderamente aporten valor para que las iniciativa pública y principalmente la privada, los vean como oportunidades que sumen a sus objetivos y aporten recursos económicos y otros importantes apoyos como la difusión.

Ahora en cuanto a la tecnología, el consumo cultural está totalmente inmerso en este ámbito, como gestores es necesario aprender, comprender y estimular el acercamiento a las nuevas tecnologías y plataformas, como lo son las RA y RV, así como mucho más recientemente el metaverso y NFT.”

Algunas de las colaboraciones recientes de Mercarte han sido con Silk, Shell, Mccormick y Natura entre otros-¿Podrías platicarnos sobre la Fundación Arte por la Vida? ¿Cuál es la relación de las prácticas artísticas con la responsabilidad social?

“Soy una fiel creyente de que el arte es un agente importante de cambio social, por ello hace 6 años creé el programa social Arte por la Vida, el cual es una Fundación sin fines de lucro y donataria autorizada, cuyo objetivo es acercar el arte y sus virtudes, a poblaciones vulnerables (específicamente a niños y jóvenes de casas hogar y adultos mayores que viven en asilos).

Arte por la Vida, es un ejemplo de la relación necesaria que existe entre el arte y la responsabilidad social, ya que justamente nos permite la transformación como individuos que se amplifica hacia el grupo y por ende a la sociedad.

Dentro de las actividades que realizamos contamos con visitas guiadas a exposiciones en museos, galerías y funciones de teatro, así como la impartición de talleres de arte y murales, a cargo de reconocidos artistas.

Hasta ahora, Fundación Arte por la Vida ha beneficiado a más de 1500 personas vulnerables, tanto en CDMX, Edomex como en Veracruz y Morelos.”

Miho Hagino: de la vida para el arte y el arte para la vida

De la vida para el arte y el arte para la vida

Miho Hagino es una artista multidisciplinaria y gestora cultural de origen japonés que reside en México desde finales de los noventa. En su obra y en los proyectos que ha ayudado a construir, podemos notar un claro sentido de conciencia e interconectividad con otras personas, insertando a su propio yo colectivo en el proceso creativo. En sus palabras, el ser una mujer inmigrante y japonesa en latinoamérica le ha traído a lo largo de la vida muchos retos, especialmente como artista, pero a su vez la ha dotado de una perspectiva única y una sensibilidad particular, presentes tanto en sus obras como en sus proyectos de arte social. Actualmente dirige el proyecto Paisaje Social, una “asociación civil sin fines de lucro creada por un grupo de artistas y profesionistas en distintas disciplinas que trabajan desde 2009, para crear plataformas culturales de acercamiento con comunidades socialmente vulnerables“ y Xunca para Tecas, un proyecto artístico y de activación económica que realiza huipil contemporáneo.

Entrevistamos a esta artista para averiguar sobre su quehacer multidisciplinario, su relación con la identidad y el lenguaje y sus vivencias en México.

-Mucha de tu obra fotográfica tiene un vínculo con la naturaleza y el paisaje,¿cuál es tu relación con estos elementos?

“Hay una diferencia del motivo de creación de los artistas orientales y de los occidentales: en el caso de los occidentales el ser humano está separado de la naturaleza y en oriente el ser humano es parte de la naturaleza. En el shintoismo la naturaleza es nuestro dios, nuestras sabiduría y acompañamiento, nuestro miedo como aprendizaje y esto se parece mucho a las culturas indígenas, donde dios es plural. No solo yo pero muchos artistas japoneses tienen un vínculo muy sensible con la naturaleza.(...) En mi caso crecí en una tierra rural al lado del bosque en Hokkaido, las casas están alejadas unas de las otras, es un lugar frío y nieva durante mucho tiempo. Esto marcó mucho mi relación con la naturaleza y se convirtió en un eje dentro de mi porque pasaba más tiempo en ella que incluso con mi propia familia.”

Paisajes / Landscapes: En todos los lugares y ningún lado / In all places and nowhere (2016-2019)

-A lo largo de todos tus proyectos un tema recurrente es la identidad propia como vehículo para empatizar con otras personas o seres, ¿podrías hablarme más al respecto? ¿está relacionado con tu historia de vida?

“Intento trabajar de forma colectiva, más allá del artista/individuo porque nosotros no existimos si no existe el otro. Desde la infancia tenía dudas sobre mi identidad. Por el trabajo de mi padre nos mudamos mucho y crecí en un ambiente poco estable.(...) En el caso de México, aunque soy japonesa, este es mi carácter y hablo japonés, tampoco soy tan japonesa porque vengo del norte de Japón, donde hay muchos migrantes. Cómo no puedo explicar quien soy mediante el idioma y las tradiciones, aprendí a compartir mi identidad mediante la comunicación con otros. Uso el arte porque es un medio que acepta un lenguaje abstracto. Antes muchas personas querían que yo abandonara mi propia vida y mi deseo, porque en japón como mujer, ¿cómo es posible que quisiera ir al extranjero a estudiar arte si ya no era joven? Mi familia y mis amigos me apoyaron y tuve la oportunidad de salir. Este tipo de situaciones son comunes para las minorías: nosotras simplemente queremos vivir tranquilas, sin violencia o discriminación.”

Fascinación (1998)

-Háblanos sobre México: ¿que te llevó a comenzar a producir obra y proyectos aquí? ¿Qué te inspira?

“Visité México por primera vez en 1993 y fue una sorpresa. Cuando llegué aquí no sabía dónde estaba, mucho menos el idioma. Me habían advertido, cuando estuve en Estados Unidos, que era un país muy peligroso. Pero al contrario, yo quise venir a ver que había. Era un mundo que nunca me había imaginado, muy distinto al mío. Estar en México me da cierta neutralidad: no es norte ni sur, ni oriente ni occidente. Puedo decidir a dónde voy y quién quiero ser como artista y japonesa.(...). Aquí puedes opinar libremente y de forma independiente. Puedes trabajar en cualquier medio artístico y exponer si tu propuesta es buena ya que hay muchas oportunidades. Las personas se preocupan de sí mismas para poder ser, cada quien con sus opiniones.”

Xunca para Tecas: Huipil contemporáneo/ proyecto de arte y reactivación económica en Juchitán, Oaxaca

-Aparte de ser artista visual has hecho curaduría y gestión cultural en varias áreas, ¿crees que estas disciplinas se complementan las unas a las otras? ¿Cómo ha sido tu experiencia?

”Esto surgió por necesidad. A principio de los 2000s el mundo del arte contemporáneo era , y lo es hasta ahora, muy patriarcal con una jerarquía donde yo no puedo pertenecer. Cuando volví a México después de estar en Japón y trabajar en Los Ángeles,tenía una frustración: me encasillaron en varias tendencias del arte occidental cuando yo tenía otra propuesta. Sentí que mi obra no iba a ningún lado y comencé mejor a trabajar con arte social y migrantes japoneses, especialmente con mujeres. Cuando empezamos con Paisaje Social, no había becas o apoyos para un proyecto como ese, se veía el arte y lo social como algo separado. Desde hace varios años esto ha cambiado y ya hay recursos a largo plazo. Llegué a la conclusión de que mi propio trabajo no debe mezclarse con estos proyectos ya que tienen una vinculación fuerte por sí mismos, separados de mi obra. Actualmente hay muchos artistas que su nuevo giro es trabajar en arte social, creo que puede llegar a ser un poco peligroso si hay un interés personal de por medio o falta una verdadera preocupación por las personas llamadas “vulnerables”, que aunque puedan tener una desventaja económica cuentan con una gran riqueza cultural.”

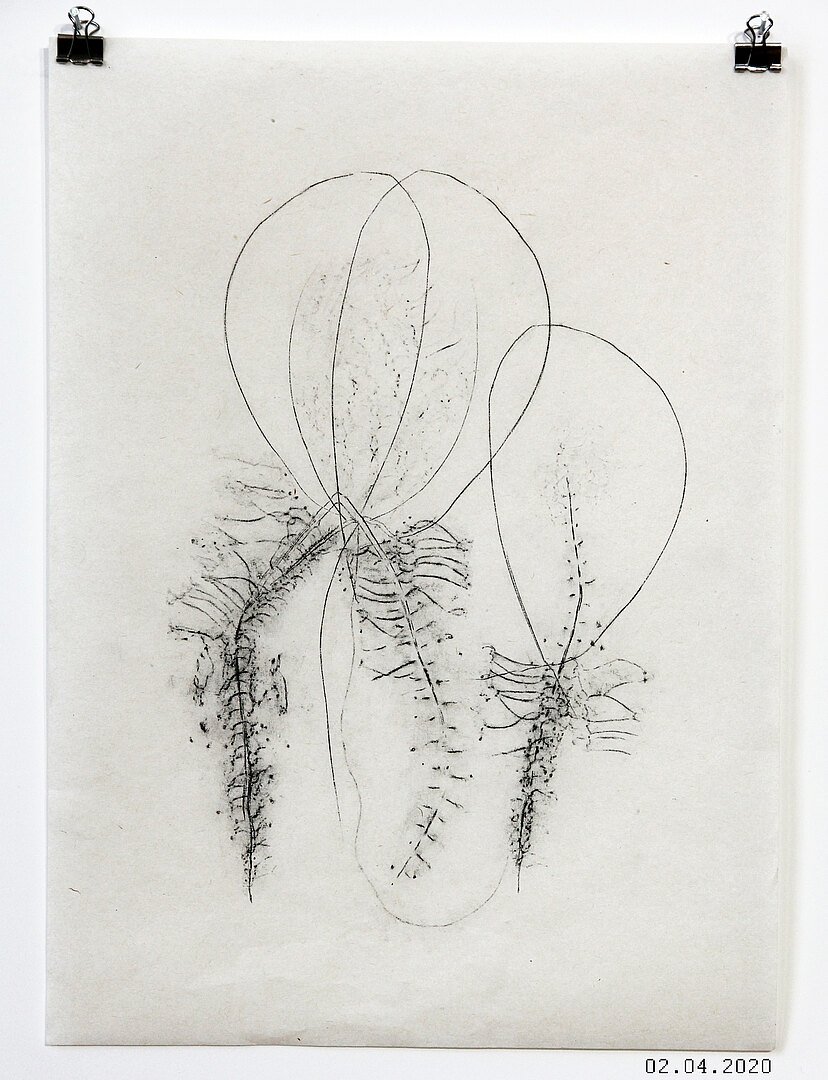

Un país en las memorias (2008-2013)

Proyecto Japón

Piezografía y grabado sobre papel algodón, video 60 minutos

Miho Hagino: from life to art and from art to life

from life to art and from art to life

Miho Hagino is a japanese multidisciplinary artist, curator and cultural manager living in Mexico since the late nineties. In her work and the projects she has helped build, there is a clear sense of consciousness and interconnectivity toward other people, inserting her own collective self in the creative process. In her own words, being an immigrant japanese woman in latin america has been challenging, specially as an artist, but has given her a unique perspective and sensibility shown in her personal works and her social art projects like Paisaje Social and Xunca para Tecas. We interviewed her to learn about her artistic endeavor, her relationship with identity and language and her life in Mexico.

-Much of your photographic work has to do with nature and landscape, what is your relationship with these elements?

There is a difference between the reason us eastern artists create and the reason western artists do: in the West the human being is separated from nature and in the East we are part of it. In shintoism nature is our god, our wisdom and company, even if we fear it we learn from it. This is very similar to the way many indigenous cultures view the world, god being plural. It’s just not me but many Japanese artists have this very sensitive relationship with nature(...). In my case I was raised on a cold rural land near the woods in Hokkaido, where houses are wide apart and snow is common. This shaped my relationship with nature and made it a central axis inside of me because I spent even more time out there than with my own family.

Paisajes / Landscapes: En todos los lugares y ningún lado / In all places and nowhere (2016-2019)

-Throughout all of your projects a recurring theme is your own identity as a wall to empathize with other people and being, could you tell me more about it? Is it related to your life story?

“ I try to work in a collective way beyond the individual artist because we don't exist and the other doesn’t. Since I was young I was doubtful about my own identity. My father’s job kept us moving around so I grew up in an unstable environment.(...). In Mexico, even if I am Japanese, my character is japanese-like and I speak the language. I am not that Japanese because I come from Northern Japan where there is a lot of migration. Since I cannot explain who I am through language and traditions I learned to share my own idea of self with communication. I use art to do so because it’s an abstract language. Before, a lot of people wanted me to abandon my own life and give up my desires because as a woman living in Japan, how was it possible that I wanted to go abroad to study art when I was not young anymore? My family and friends supported me and I got the chance to go out. This type of situations are common for minorities: we just want to live in peace, without violence or discrimination.”

Fascinación (1998)

-Let's talk about Mexico, why did you start working here in the first place? what inspires you?

“I visited Mexico for the first time in 1993 and it was a surprise. When I arrived I didn't know where I was and I didn't understand the language. I had been warned, when I was in the U.S., that this was a very dangerous country. On the contrary, I wanted to see what this country was about. It was a place I couldn't have imagined, very different from where I come from. Being in Mexico gives me a sense of neutrality: this place is nor North or South, nor East or West. I can choose where to go and who to be as a Japanese woman and an artist(...). Here i can freely share my opinions and be independent. You can actually work in any artistic medium if your proposal is good, there are a lot of opportunities. People worry about themselves to be able to exist on their own terms and with their own opinions.”

Xunca para Tecas: Huipil contemporáneo/ proyecto de arte y reactivación económica en Juchitán, Oaxaca

-Aside from being a visual artist you have worked as a curator and cultural manager in various areas, do you think these disciplines compliment each other? What has been your experience?

“This happened because of necessity At the beginning of the 2000s, and it is till this day, the contemporary artwork has a very patriarchal, rigid hierarchy that could not belong to. When I came back to Mexico after being in Japan and working in L.A. I was frustrated: my work and I had been classified in the western art history narrative when I had a different view. I felt like my work was going nowhere and I started working with social art and Japanese migrants, especially with women. When the Paisaje Social Project started, there was no funding support from the government because the art and the social spheres were seen as separate. Recently this has changed and now there are long-term resources available. I came to the conclusion that my own artistic work should not be mixed with these projects because they are strong on their own. Right now there are many artists jumping on the social art trend but that can be dangerous if there are personal interests and a lack of concern for the so-called “vulnerable” people, because even if they are economically disadvantaged, they have a rich cultural heritage.”

Un país en las memorias (2008-2013)

Proyecto Japón

Piezografía y grabado sobre papel algodón, video 60 minutos

La Fundación Andy Warhol para las Artes Visuales: Legado e Identidad

La Fundación Andy Warhol para las Artes Visuales: Legado e Identidad

La Fundación Andy Warhol para las Artes Visuales se fundó en 1987. La misión principal, de acuerdo con Warhol quien estuvo muy involucrado en su planeación, es el del avance de las artes visuales. La fundación otorga apoyos tanto a artistas como a organizaciones de forma equitativa y flexible: hasta la fecha ha otorgado más de $250 millones en efectivo en forma de apoyos para más de mil organizaciones de arte en 49 estados de Estados Unidos e internacionalmente. Ha donado también 52,786 piezas de arte a 322 instituciones alrededor del mundo. La fundación se enfoca en la labor de artistas visuales, otorgándoles los medios para experimentar y profundizar en su labor. ya que se enfocan en otorgar fondos a proyectos de carácter crítico que “acepten las marginalización sistémica de nuestra cultura hacia los artistas por su raza, género, religión, edad, discapacidad, orientación sexual y/o estatus de inmigración, entre otros factores.”

La selección ocurre dos veces al año, en mayo y septiembre. Posteriormente los ganadores serán anunciados en Enero. Un requisito importante es que el apoyo económico no debe exceder el 25% del costo de todo el proyecto y que aunque su labor se enfoca en Estados Unidos, otros proyectos internacionales pueden aplicar aunque se requieren más requisitos. Anualmente se otorgan más de 100 apoyos a artistas, organizaciones de arte y curadores por todo Estados Unidos.

Parte de la visión de la fundación, al igual que la de Warhol, era poner al artista como individuo y parte central del proceso creativo, pero entendiendo cómo sus acciones y propuesta pueden hablar de una problemática tanto general como compleja. La fundación busca auxiliar a los artistas e instituciones en toda las fases de su proyectos, desde la realización creativa hasta la museografía, residencias artísticas y la difusión. Por ello otorgaron una serie de apoyos y premios que se adaptan a las necesidades de cada postulante, los cuales son la Curatorial Research Fellowship (investigación curatorial), Exhibition Support (apoyo en la exhibición) y los programas de apoyo de año múltiple. Además, los artistas pueden acceder a un programa (Re-granting program) para volver a obtener apoyo de forma regional. A esto se le suman las Iniciativas espaciales en los rubros de Capital Creativo, Common Field (organizaciones de arte independientes) y el Arts Writers Grant para escritores.

“El compromiso de la Fundación de apoyar a los artistas financiando las instituciones que incuban, promueven, exhiben y realizan su labor de forma crítica es firme. Las organizaciones de arte sin fines de lucro enfrentan retos constantemente debido a las situaciones políticas, económicas, sociales y culturales del momento. Al mismo tiempo, los artistas necesitan una comunidad que los apoye y un impulso creativo que estas organizaciones pueden proveer.”

Joel Wachs, Presidente

Los objetivos y misión de cualquier fundación deben, en el mejor de los casos, ser congruentes. Esto quiere decir que la transparencia de los procesos internos de la organización deberán reflejar resultados reales y tangibles. Esta fundación se diferencia de otras de su tipo de la misma forma que Andy Warhol lo hizo con otros artistas de su época: contando con una excepcional capacidad para entender las problemáticas de su tiempo y respondiendo con una sensibilidad incisiva. Esto se refleja en la producción de obra del artista, la publicidad, el diseño de productos y su incursión en lo audiovisual. La conciencia de Warhol sobre los medios de producción masivos y la cultura de consumo que son el hilo conductor de su obra y esto se refleja en la labor que realiza la fundación para la concesión de licencias con piezas del artista o su propia imagen:

“La fundación es el guardián designado para salvaguardar el legado de Warhol y su galardonado programa de licencias le hace homenaje a la forma sofisticada en la que el artista combinaba el arte y el comercio. Esto a su vez genera ganancias que ayudan a la fundación y la extensa labor filantrópica que realiza. Esta es una responsabilidad que la fundación realiza de forma cuidadosa y rigurosa, pero también creativamente, tomando en cuenta el espíritu rebelde de Warhol combinado con su inventiva perspectiva empresarial.”

Adaptar la imagen de Warhol como un producto cultural contemporáneo que nos lleva continuamente a evaluar y valorar su trabajo. Por un lado, la fundación ha realizado colaboraciones creativas con marcas de lujo como Comme des Garçons, Supreme, Calvin Klein y Dior. Mientras que estas acciones de gran valor económico mantienen funcionando la organización y circulando la imagen del artista, la fundación colabora con Artstor, un archivo de imagen y recursos digitales para la educación artística, obsequiando 30,000 imágenes d e alta resolución de piezas del artista y 130,000 fotografías.

El Andy Warhol Museum en Pittsburg fue co-fundado por la Fundación Andy Warhol, la Dia Art Foundation y el Instituto Carnegie. Este espacio es el repositorio más grande de la obra del artista, contando con más de 500, 000 objetos y en un inicio la fundación donó más de 3,000 obras al museo, al igual que objetos personales y archivos. Aunque actualmente el museo es una institución independiente, el espíritu innovador y crítico que ha establecido los lineamientos de la labor institucional de la fundación, se ve reflejado en las líneas curatoriales del espacio y sus actividades. El museo se convierte en un espacio que busca profundizar en la práctica y producción del artista a la vez que funge como un archivo de la vida y la época del artista:

“Él era (...) un coleccionista obsesivo, guardo periódicos, recortes de prensa, posters, fotos y otras objetos. Estos registros históricos tan vitales fueron preservados en su Centro de Estudios, especialmente diseñado para esta labor, al igual que 610 Cápsulas del Tiempo del artista, donadas por la fundación. En 1970 el artista comenzó a armarlas en 1970 con correspondencia, recibos, fan mail, panfletos de exhibiciones, mensajes telefónicos y tiras cómicas. En el 2007 la Fundación le otorgó al museo un apoyo de $625,000 dólares para desarmar estas cápsulas y su contenido, un proceso que continúa hasta hoy en día. Los archivos también incluyen las bibliotecas personales del artista, sus entrevistas en revistas y muchos objetos personales que incluyen materiales de artes, 175 frascos para galletas y varias pelucas.”

Andy Warhol: Polaroids XL (2015)

La fundación Andy Warhol se posiciona como una de las más importantes en el mundo del arte contemporáneo y esto no es solo por su labor, sino por la misma construcción de identidad que han logrado a lo largo de los años como una organización de vanguardia que busca satisfacer las necesidades de los artistas del momento. Crear proyectos y dar a apoyos a artistas es su misión principal, pero esto se logra difundiendo la obra de Andy Warhol no solo como artista en sí, sino como su visión del arte y la producción artística estaban íntimamente ligadas con su vida. La fundación toma todo esto en cuenta, creando un espacio crítico y colaborativo que busca preservar el legado de Warhol de una forma dinámica más allá de un archivo o una remembranza.

Fuentes: https://warholfoundation.org/

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts: Legacy and Identity

Legacy and Identity

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Art was created in 1987. Their main mission, according to Warhol, is the advancement of the visual arts. This foundation gives grants to artists and organizations in an equal and flexible way: they have given more than $250 million dollars in cash in form of grants to more than a thousand art organizations, artists and curators in 49 states throughout the U.S. and internationally. They have donated 52, 786 art pieces to 322 art institutions all over the world. they focus on funding projects by visual artists that “acknowledge our culture’s systemic marginalization of artists because of race, gender, religion, age, ability, sexual orientation, and/or immigration status among other factors.”

Selection happens twice a year, in May and September, and the grantees are announced the following January. An important requirement is that the grant doesn't exceed more than the 25% of the overall cost of the project and even if their work focuses on funding projects in the U.S., international artists can apply. Annually the foundation gives more than a hundred grants to artists, curators and art organizations.

Part of the foundation's vision, according to Warhol as well, is to make the artists recognize themselves as an individual in their creative process but aware of how their actions and work can talk about a general, complex issue that affects society. The foundation aids artists and organizations in an array of ways, from creative planning, to museography and artistic residences. They support artists with various grants which are the Curatorial Research Fellowship, Exhibition Support and a multiyear program. Grantees can also apply to be part of the regional re-granting program and a series of Special Initiatives like Creative Capital, Common Field and the Arts Writer Grant.

“The Foundation’s commitment to supporting artists by funding the institutions that incubate, encourage, exhibit and critically engage their work is unwavering. Non-profit arts organizations face profound challenges due to the political, economic, social and cultural upheavals of our current moment. At the same time, and more than ever, artists need the supportive community and creative encouragement that these organizations provide.”

Joel Wachs, President

The objectives and mission of any foundation should, in the best of cases, work cohesively with one another. This means that the transparency of the organization's internal work bust reflects on the real and tangible results. This foundation is different from its own kind in the same way Andy Warhol was related to other contemporary artists of his time: having an exceptional capacity to understand the social issues of his time and responding to them with an incisive sensibility. This is seen in his work production and his incursion in publicity, design and video. The awareness Warhol had about mass production and the culture of consumerism help define his work as well as in the foundation Licencing Programs:

“The Foundation is the designated steward of Warhol’s legacy, and its award-winning licensing program pays homage to the artist’s sophisticated melding of art and commerce, fine art and popular image-making—while also generating revenue to support the Foundation and the extensive philanthropic work it does. This stewardship is a responsibility that the Foundation approaches thoughtfully and rigorously, but also creatively, taking a cue from Warhol’s non-conformist spirit and his inventive entrepreneurial approach.”

Adapting Warhol’s image as a cultural product allows the public to constantly revalue his work. On one hand, the foundation has collaborated creatively with luxury brands like Comme des Garçons, Supreme, Calvin Klein and Dior. This gives the foundation enough economic support to keep founding other projects such as their collaboration with Arstor, an extensive image resource site for educational purposes, donating 30,000 images of Warhol’s work and 130,000 photographs as well.

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg was co-founded by The Andy Warhol Foundation, the Dia Art Foundation and the Carnegie Institute. This space is the biggest repository of the artist’s work with more than 5000,000 objects. At the beginning the Foundation donated more than 3,000 pieces, archives and personal belongings to the museum. Even if now the museum is an independent institution, the innovative and creative spirit in the institutional labor the foundation makes is reflected in the curatorial work and activity the place offers. The museum is a place that wants to deepen the research on the artistic production and practice of the artist, as well as his archive:

“He was (...) an obsessive collector, saving periodicals, press clippings, posters, photos, and other ephemera. These vital historical records are preserved in the museum’s specially designed Study Center, along with 610 of Warhol’s Time Capsules (donated by the Foundation), which the artist began assembling in 1970 by tossing correspondence, receipts, bills, fan mail, exhibition announcements, phone messages, and other everyday tidbits into cartons, which he then sealed. In 2007, the Foundation provided the museum with a $625,000 grant to help fund efforts to unseal the boxes and archive the contents—a process that is still ongoing. The archives also include Warhol’s libraries, a full run of Interview magazine, and hundreds of personal items, including art supplies, 175 cookie jars, and several wigs.”

Andy Warhol: Polaroids XL (2015)

The Andy Warhol Foundation positions itself as one of the most relevant associations in the contemporary art world not just because of their work but for the institutional construction of identity through the years and how they meet the needs of artists of our time. Creating projects and helping artists is their main goal, but this is made not just by promoting Warhol’s work as an artist, but understanding how his vision of art shaped his own life and artistic production. The Foundation takes all of this into account, creating a collaborative and critical space to preserve Andy Warhol’s legacy in a dynamic way beyond an archive or an act of memory.

Source: https://warholfoundation.org/

Omar Rosales: matter and emptiness as a vital experience

Matter and emptiness as a vital experience

Thinking about artistic production or practice as an exercise or an always changing activity is part of a curator’s work. More than making a timeline about an artist “evolution” or their academic merits,it is about understanding creative practices as part of a vital attitude present in the life, experience and trajectory of an artist. Omar Rosales is a Mexican artist that studied in the San Carlos Academy and later on got a PhD in sculpture by the Hiroshima City University in Japan. During the seven years he lived in that country he saw how his own vision of art and practice started to change and when he returns he created the first gallery focused on contemporary japanese art in his home country. In this interview we will talk about his work and how his experiences have modified his curatorial and artistic practices.

How did the GAMEX project came to be and how was the management of it?

During that time i was living in Japan and I was doing research on Japanese art for my master’s degree. This project began as a part of that research because it was important for me that every artist used this specific plastic sphere used to dispense toys in Japan, called gacha gacha. At first I invited mexican artist to work with these spheres and it worked in a massage-in-a-bottle sort of way. I asked the question “¿What is emptiness?” and it was answered through the capsule and then the artist answered as well in different ways.

The management of the project was through the artist’s cooperation, everyone looked for ways to get their work sent to Japan. I had a collaborator in Mexico City who helped me create an exhibit there apart from the one in Hiroshima. We had good results and a lot of people showed up to both inaugurations.

Omar Rosales, Astrolmeca (2013)

How did your own artistic practice and vision changed after studying and living in Japan?

During my college years in Mexico there were a lot of academic deficiencies because a lot of teachers were not interested in the study of aesthetics. Japanese culture has a very particular relationship with materials, how we treat them and our own sensibility and that is reflected in my work. I had to restructure the whole concept of what i thought art was and i focused on the concept of beauty and matter. I am also interested in the concept of religion through the perspective of zen buddhism. This new vision of art made me understand the importance of matter from which works are made. In my work the Japanese influence might not be direct, visually speaking, but it has affected my work in an indirect way.

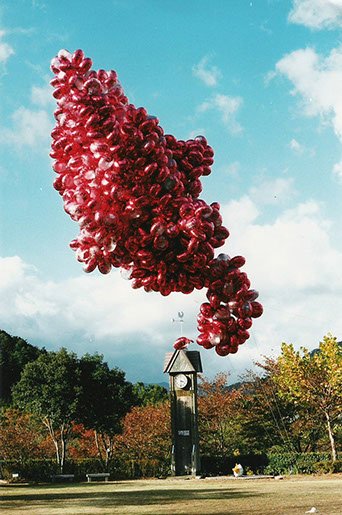

A thousand equals one (1999), Uwa park, Japón

Much of your work explores the concepts of matter and emptiness, ¿could you tell me more about that?

I use a lot of transparent resin that allows me to see the interior of the pieces. I see this as a possibilite. Sometimes emptiness has negative connotations, like drifting away or a lack of presence or essence but I think this contained energy has millions of different ways to be interpreted. There is a relationship between the material used and the internal and external space: we can see inside the work despite its solidity, creating meaning. Form defines space and matter. In my latest work I still work with these ideas but now I add flowers inside these structures for contrast and to show the relationship of the artificial, nature and the material. Industrial resin accentuates the flower’s beauty, so different from the interior composition of the shape. This relationship might seem like a contradiction, but inside the sculptures a harmonious universe with various elements is created, all contained through form.

Cipher (2019-2020), Resina transparente y pétalos de rosa

What is the relationship between your curatorial and artistic practice? Have they influenced each other?

I became a curator in a very intuitive way through the GAMEX project and through the years my experience in this field has grown as well as my artistic one. The go together because i believe the first curatorial exercise every artist makes us with their own work: one is curator and critic of their own pieces when you select them, as well as the discourse artist’s work and different projects. My formation in japanese art and my PhD in traditional japanese sculpture has allowed me to curate works related to japanese art or from mexican artists who talk about it as well. I create different types of narratives related to japanese art and culture, focusing in mexican and japanese artist who have an interest in each other’s culture.

Red enzo (2021), Tinta sobre papel

Omar Rosales: materia y vacío como experiencia vital

Materia y vacío como experiencia vital

Entender la práctica y producción artística como un ejercicio o actividad en constante cambio es parte del quehacer curatorial. Más que trazar una línea del tiempo sobre la “evolución” del trabajo de un artista o sus méritos académicos, mucho del trabajo de la curaduría es situar la práctica creativa como una actitud vital presente en la vida, experiencia y trayectoria del artista. Omar Rosales es un artista mexicano que estudió en la Academia de San Carlos y posteriormente realizó estudios de posgrado sobre escultura japonesa en Japón (Hiroshima City University). Durante los siete años que vivió en ese país, vio cómo su propia visión del arte y su propio trabajo fue poco a poco cambiando y al volver a México, decidió crear la primera galería enfocada en arte japonés del país. En esta entrevista hablamos sobre su trabajo y cómo sus experiencias han modificado su práctica artística y curatorial.

¿Cómo surgió la idea de GAMEX y cómo fue gestionar el proyecto?

La idea surgió porque en ese tiempo yo vivía en Japón y me encontraba investigando sobre el vacío en el arte japonés para mi maestría. Este proyecto surgió como una parte de esa investigación ya que lo importante era que cada artista utilizara una esfera de plástico vacía que en Japón se usa para dispensar juguetes, llamada gacha gacha. Yo invité en la primera parte a artistas mexicanos que trabajaran con las esferas y funcionó un poco como un mensaje en una botella vacía que se tira en el océano para ver quién responde, quién la encuentra. Yo hacía una pregunta: ¿qué es el vacío?, recibía la cápsula y ellos contestaban , obteniendo muchas respuestas.

El proyecto se gestionó entre los artistas a manera de cooperación, cada uno buscó la manera de enviar sus obras. Yo tenía un colaborador en la Ciudad de México para coordinar la exposición en la ahí aparte de la de Hiroshima y así se pudo llevar a acabo. El resultado fue bastante bueno, la gente respondió muy bien y fue mucha gente a ambas inauguraciones.

Omar Rosales, Astrolmeca (2013)

¿Cómo cambió tu propia práctica artística y visión del arte haber estudiado y vivido en Japón?

Durante mis estudios en México hubo muchas deficiencias ya que muchos profesores realmente no enseñan la parte estética, tal vez porque no lo saben. Me encontré con una cultura que tiene una relación muy particular con los materiales, con el trato, con la sensibilidad hacia estos, y esta sensibilidad se ve reflejada en lo que yo hago. Volví a reestructurar todo lo que yo pensaba respecto al arte, y me enfoqué mucho en concepto de belleza y lo material al igual que en lo religioso desde la perspectiva del budismo zen. Esto creo en mí una visión del arte que toma muy en cuenta la materia con la que están hechas las obras. En mi obra no se ve directamente la influencia de esta cultura, visualmente hablando, pero sí de forma indirecta a través de la sensibilidad hacia los materiales.

Mil es igual a uno (1999), Uwa park, Japón

3)Mucha de tu obra explora los conceptos de materia y vacío, ¿podrías contarme un poco más sobre esto?

Utilizo mucha resina transparente que permite observar el interior de las piezas. Veo esto como una posibilidad. A veces el vacío se entiende como algo negativo, una falta de rumbo, de presencia o de esencia, pero al contrario, esta energía contenida por la forma tiene posibilidades infinitas de ser interpretada. Hay una relación entre el material que se usa y el espacio interno y externo: se alcanza a ver en interior de la obras aunque son sólidas, dándole sentido. La forma delimita los espacios y la materia. En mis últimos proyectos sigo trabajando con ello pero ahora incluyo flores en el interior de las estructuras como contraste y para mostrar una relación entre lo artificial y la naturaleza y el material. La resina industrial resalta la belleza de las flores que contrasta con la composición interior de la forma. Esta relación en principio parece contradictoria pero en el interior de las esculturas se crea un universo único donde los elementos conviven armoniosamente contenidos por la forma.

Cifra (2019-2020), Resina transparente y pétalos de rosa

¿Cuál es la relación entre tu práctica curatorial y tu práctica artística? ¿Se han influenciado mutuamente?

Llegué a la curaduría de forma muy intuitiva por el proyecto de GAMEX y a lo largo de los años me he vuelto curador a la par de mi carrera artística . Van de la mano porque el primer ejercicio curatorial que hace un artista es su propio trabajo: uno es crítico y curador de su propia obra cuando seleccionas las piezas que vas a usar, el discurso y haces la museografía. Después dependiendo de las circunstancias puedes establecer líneas curatoriales para obra de los demás o de un proyecto. En mi caso por mi formación en arte japonés y doctorado en escultura tradicional japonesa toda la curaduría que he hecho tiene que ver con arte japonés o con artistas mexicanos que hablan de Japón. Creo discursos y propuestas relacionadas con la cultura del arte japonés y como se entiende en México enfocándose en propuestas de artistas mexicanos o japoneses que tengan un vínculo con cualquiera de estas dos culturas o quieran establecerlo.

Enzo rojo (2021), Tinta sobre papel

The Pollock-Krasner Foundation

Through the generosity of Lee Krasner, one of the foremost abstract expressionist painters, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation was established in 1985 to provide financial resources to individual visual artists internationally.

In the Great Depression during the 1930’s, work opportunities for artists were almost non.existent. Therefore president Franklin D. Roosevent’s administration introduced a series of programs for the “art workers' 'from 1935 to 1948. The Federal Art Project from the WPA (Works of Progress Administration) supported artists based on their artistic merit and economic needs, giving them minimum wage. This was a pivotal moment that allow the development of abstract expressionism in the Us because artists acquired some form of creative and experimental freedom since they weren’t dependent on the art market anymore:

“Franklin D. Roosevelt spelled out the rationale for supporting artists, marginal figures suspected in some quarters of subversive intent. “The Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration,” said the president, is a practical relief project which also emphasizes the best traditions of the democratic spirit. The WPA artist, in rendering his own impression of things, speaks also for the spirit of his fellow countrymen everywhere. (...) The WPA artist exemplifies with great force the essential place which the arts have in a democratic society such as ours.”

In the same way the WPA helped artists in need in the past, the Pollock-Krasner foundation helps artists and organizations so they can continue their work. By 1988 the foundation had helped about 300 artists by giving away a total of 1.5 million dollars. Currently the Pollock-Krasner Grant is open throughout the year and lasts a year as well. The foundation focuses on the work of the painter and after applying, the Selection Committee gives the grantee up to 30,000 dollars. Some of the criteria taken into consideration for being chosen is the recent professional exhibition in museums and galleries.